Animals that live on 32,000 acres from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, 32,000 acres in North Virginia are linked by one thing: the threat of extinction.

Nestled in Blue Ridge mountain buttresses, more than 20 species at risk of extinction, including Mongolia Przewalski Horse, which disappeared from nature at the end of the 1960s, lived in the field of the Institute. There are red pandas, fiery wolves and darkened leopards, to name any more.

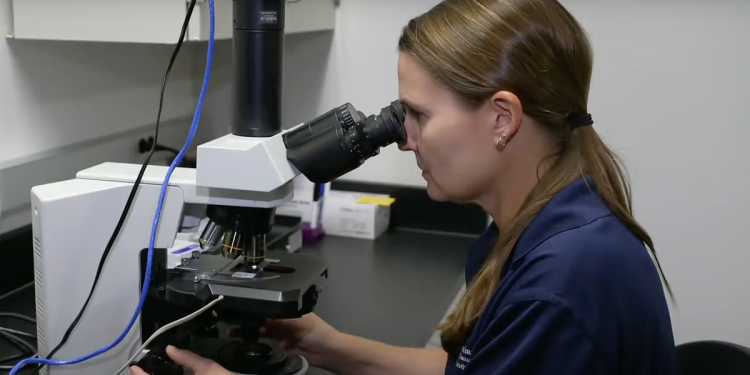

The Institute studies reproduction, ecology, genetics, migration and sustainability of the conservation of a species, with the ultimate objectives of saving the fauna of extinction and the formation of future conservationalists. In some cases, scientists are responsible for breeding and reintroductions in their habitats.

But those who work to keep these species and remove them from the list of endangered species are always affected by the speed at which species disappear.

“We see species disappear at 10, 100, to 1000 times the normal substantive rate,” said the Biologist for the Conservation of the SCBI, Melissa Singer, at CBS News.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature warned at the beginning of 2025 than 28%, more than 47,000, of species evaluated in the world run a risk of extinction. This number includes more than animal species, showing crucial insects, plants of plants and trees are also threatened.

“So we think, okay, well, we lose the species here and there, you know, there are many other species,” said, “but the fact is that when we lose a species, it has cascade effects.”

An excellent example of this effect is with the ferret of black feet, which originally lived in the great North American plains but has been disappearing since 1967.

While the species remains on the list threatened, its population has increased since the start of preservation efforts at the Institute.

“Each ecosystem animal is important for this ecosystem,” explains Adrienne Crosier, biologist of the cheetahs in SCBI, “they all have a really important role to play.”

Regarding the ferret of black feet, Crosier says that it is “a mixture of predator and prey for other larger carnivores”, which means that other animals are left without food in the absence of the ferret.

“Each time you completely remove a species from the ecosystem, you cause an imbalance in this ecosystem,” explains Crosier.

The Crosier team currently takes care of around 60 ferret kits, which will be released in Colorado Wild in the fall.

“Whenever we have a native offspring, I have the impression that we have done our job,” said Crosier with a smile.