About 1,500 health centers financed by the federal government who serve millions of low -income people are faced with significant financial challenges, according to their leaders, as the government is aggravating other reductions in their income.

Some of these community health centers may have to reduce medical and administrative staff or reduce services. Some could possibly close. The result, warns their lawyers, can be additional pressure on the already crowded emergency rooms of the hospital.

“This is the worst moment of all years I work in health care,” said Jim Mangia, president and chief executive officer of St. John’s Community Health, a network of 28 clinics that serves more than 144,000 patients in Los Angeles, Riverside and San Bernardino in California. “We are faced with federal cuts and extreme state cuts that will have an impact on services.”

St. John’s and other federal skilled health centers offer primary care and a wide range of other services free of charge or on a scrap fee scale. At the national level, they see nearly 34 million patients in the most ill -served areas in the country.

The federal funds go through two primary routes, which are both faced with challenges: subsidies paid in part by the Federal Community Health Center Fund and reimbursements for patient care thanks to programs like Medicaid, which provides health insurance to low -income and disabled people. Medicaid is jointly funded by states and the federal government.

The congress recently approved the subsidy in Dribs and Drabs. In March, legislators extended the funds until September 30. This money expired after the congress controlled by the Republican did not adopt a financing law, which led to a closure of the government.

Defenders say that health centers need long -term financing to help them plan with more certainty, ideally thanks to a multi -year fund.

The safety net of the health center faces “several layers of challenges,” said Vacheria Keys, vice-president of associations and regulatory affairs of the association.

The new expenditure law that Republicans call the “Big Beautiful Bill Act” will considerably reduce Medicaid, increasing the second set of threats to health centers.

Medicaid represented 43% of $ 46.7 billion in health center in 2023.

Lawyers have declared that the lower payments of Medicaid will exacerbate a gap between funding and operational costs.

The financing of labor programs is also necessary to support the provision of health services while centers have trouble hiring and retaining workers, said Feygele Jacobs, director of the Geiger Gibson program in Community Health at George Washington University.

The first clinics of this type opened in places like Massachusetts in the 1960s. Congress generally funded them by bipartite support, with minor fluctuations.

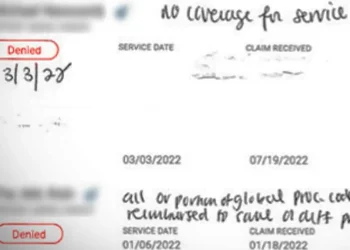

This year’s struggle started when the Trump administration froze domestic aid through a January memo, which prevented certain centers from receiving already approved subsidies. Consequently, certain health centers in states such as Virginia have closed or merged operations.

The future cuts should also arrive at a time when patients will face new requests and challenges. Medicaid changes in the tax on the tax and expenses of President Donald Trump include the registration requirements of Medicaid in order to report their work or other hours of service to maintain their advantages.

Meanwhile, more generous tax credits, the Biden administration and the congress provided consumers to help pay health insurance for the affordable care law should expire at the end of the year. The costs of certain consumers will increase if the congress does not renew them.

One of the reasons why the government has closed is that Democrats want to extend tax credits, which protect consumers against higher insurance costs. The republican financing bill did not include extension; The leaders of the Republican Congress say that the question should be addressed separately.

Consumers “will need more support than ever,” said Jacobs, noting that Medicaid cuts and the expiration of higher tax credits “will potentially make people out of coverage.”

Ninety percent of the patients in the centers have income which is double the level of federal or less poverty, and 40% are Hispanic.

“We also receive 300 calls per day of patients concerned about their coverage,” said Mangia, from St. John’s.

The Republicans do not directly target the centers, although they have supported the Medicaid cuts which will affect the finances of the clinics. Many Republicans say that Medicaid spending has increased and that the program growth will make it more sustainable.

State and local support

While pleading for longer -term federal funding, the centers also turn to their community and local governments for support.

Some states have already taken measures during the finalization of their annual budgets. Connecticut, Minnesota, Illinois and Massachusets have allocated money to the centers. Maryland, Oregon and Wisconsin have also provided support to health centers.

The question is how long will the money last.

While some states have strengthened their support for the centers, others go in the opposite direction. Anticipating the impact of Medicaid cuts, states and California have made their own cuts on the program.

The office of the governor of California Gavin Newsom, the Federal Ministry of Health and Social Services and the Federal Health Resources and Services Administration have not responded to requests for comments.

In Los Angeles, Mangia said, a potential solution is to work with partners at the county, noting that the County of Los Angeles has around 10 million residents.

“We can tax ourselves to increase the financing of health services,” he said.

Health center leaders build a coalition that, hopefully, “will include the main stakeholders in the county health system – community health centers, clinics, hospitals, doctors, health plans, unions – to start the process to fill in a voting petition, declared Mangia. The objective: ask the question of taxes for health centers on the voting bulletin and let voters decide.

“We learn that the federal government and the state government are not reliable when it comes to continuing to finance health care,” said Mangia.