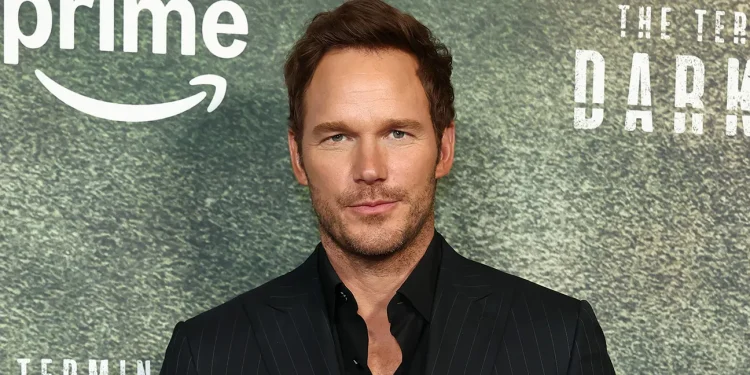

The cast and creative team behind the upcoming Amazon MGM Studios film Mercy took the stage Thursday for a panel at New York Comic Con to discuss their unique approach to filming the upcoming title and reveal the film’s trailer.

Pratt, his co-star Kali Reis, director-producer Timur Bekmambetov and producer Charles Roven were present at the panel held at New York’s Jacob K. Javits Convention Center on the upcoming film, which bows January 23, 2026. Set in 2029, it follows Pratt’s LAPD detective who wakes up strapped to an execution chair. He is on trial for the murder of his wife and has only 90 minutes to prove his innocence in the face of an advanced AI system known as Judge Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson), who acts as the jury’s literal judge and executioner.

The panel kicked off with a video message from Ferguson, who apologized for not being present, then showed off some “stunning footage,” which Pratt quickly appeared to reveal, including a first look at the film’s nearly three-minute trailer.

“It was a departure for me,” Pratt noted. “He’s a homicide detective in the near future, and a guy who’s seen and experienced a lot. He’s part of this special new Mercy program they’ve designed, basically using AI to modify their core system to be more efficient and to deal with the increase in capital crime in this version of Los Angeles. They just want to get these murderers off the streets and send a message.”

“There is something new for Chris in this film. This is his next iteration. He plays a dark and very vulnerable character in a very dramatic story,” Bekmambetov said, discussing the film’s casting. As for the rest of the cast, Bekmambetov stressed that he chose them “because they are very different performers.” “(Chris is) famous for his action films, but he plays a dramatic role, and he’s literally in the electric chair for 90 minutes. Kali plays his partner, helps him, we think. And Rebecca is an AI judge. She’s smart and we’ll get to know her heart.”

Reis, speaking about her character, shared that “she’s very loyal, but she also has certain things about her that you have to find out, I had to find out by reading the script,” Reis said. “The script gave me a baseline that allowed me to dig deeper, to build her story, because there’s a reason she believes in this court so much.”

While discussing the influence of the film’s runtime on the narrative, the director noted MercyThe 90 minutes is “a great tool, because we were limited. We had a rule that we had to tell the story in real time. It’s 90 minutes of this clock in this courtroom. It’s a practical question, but we also live in today’s world where I think AI is coming. It’s knocking on the door, and we don’t have time to figure out what’s going to happen, how we will live in the world, whether AI will be our friend or AI will be our enemy, or AI will be our child. But we have to teach him how to behave.

For producer Roven, the AI element was part of the reason he signed on. “At the time we had the pitch, people were talking about AI, but that wasn’t really happening yet. Then, by the time we got the script and started talking about the movie, all of a sudden companies were really into AI, and the future was definitely not that far away,” he said. “I think the fact that the film is set in 2029 – every day, every week, every month that goes by, there’s something more that makes our film real.”

“The thing you’re going to talk about is: Is this going to happen? » he added later in the panel. “There’s a lot of talk about if we were to try it, because of what it would have on time and space in terms of having someone who is an AI – even calling it someone, it’s really not – this piece of equipment that can actually, in an instant, merge all of this evidence and find that this person is most likely innocent, or most likely this person is guilty. Is that good? Is it bad?”

Much of the rest of the panel focused on the film’s distinct visuals and the process of filming a story that explores, in part, how life on screen overlaps with physical life. “We currently live half our time in the physical world,” said the film’s director. “I spend half my time in a digital world. That means half of the most important events in my life happen, not in the physical world.”

In the film, that translates to “sometimes up to 1,000 screens in front of me of this character’s digital life over the last 10 years, used as evidence against (him),” Pratt said. “We had to film me in a chair, but we had to film every moment that would then be put into post-production and provided: me yelling at my wife on my daughter’s Instagram, her secret Instagram page that I find out she had, or various FaceTime calls stored in the cloud that are being used as evidence against me. All my friends, all my family, what they said, the security footage,” he explained.

Beyond what his character sees on those screens, Pratt’s cop interacts not only with Ferguson’s AI, but also with his character’s cop partner, an experience Pratt calls “a very high production value Zoom session of two people on two different sets,” with Reis “basically this projection hologram” with the actress filmed on a separate set “and her image was projected so I could see her, so I was acting in front of her.”

“A lot of what you see is his view of me. We did takes that were sometimes 50, 60 and 70 minutes long, so we shot the whole thing almost like a play until the third act,” he added. “We achieved everything, which was an incredible challenge and something different than anything I had ever done before.”

Later in the panel, the director and producers delved deeper into how they combined practical effects and green screen effects, as well as the film’s IMAX experience, and how the director’s interest in the lives of the people on screen influenced the film and filming.

“We really shot downtown. There were about five, six days of shooting in the morning because we were trying to keep magic hours,” Bekmambetov explained. “And then we had unique technology to combine what we had shot with the virtual production footage. Everything we had shot in the city was projected, and there was a track on stage where the action was happening… Then we had a visual production session and, of course, the visual effects helped us a little.”

“It was the first time we did that much footage on what we call a volume scene, which was taking things that we were going to film and putting them on screens,” Roven said. “We were not only in the second unit using vehicles, but we were bringing these vehicles onto the volume stage and putting them on rollers. There’s a scene in the movie where…(a) truck hits a police car and the police car goes into a building where people are dining, and it drives a number of them out. We shot that for real on the volume stage, with the truck, with the police car going into the building. Normally this was in the area where the team was looking at the plan, so we had to be very careful because we almost took out the crew.

He continued: “The whole scene took about three minutes to shoot, and that’s the other thing about making a movie on a volume scene. Even if you go out and shoot bits of it elsewhere, on this scene things happen very quickly.”

Bekmambetov also noted that they used robot dogs to help film at least one sequence. “We used robot dogs, perhaps for the first time in cinema history,” the director said. “The cameramen were robot dogs because I used the footage of the robot dogs reviewing the extras in a crowd across the stage and filming them. The way I directed the robot dogs was I just told them what I wanted. I said, ‘Go out there and film these guys,’ and it happened.”

As for how the public will experience this film, the panelists stressed that it is necessary to see Mercy in IMAX. “The experience will give you a real sense of what Chris is experiencing in the chair. Because these screens won’t just come to you in 2D. They’ll almost feel like they’re coming out of the movie screen and toward the audience,” Roven said.