The Iron Age was one of the most important eras in human history, and researchers may have discovered the secrets of how we left the Bronze Age behind – thanks to a 3,000-year-old foundry called Kvemo Bolnisi in southern Georgia.

It’s a site that has been studied before, but anthropological archaeologists Nathaniel Erb-Satullo and Bobbi Klymchuk, from Cranfield University in the United Kingdom, wanted to take a fresh look at the evidence.

The location was previously thought to produce iron, due to the large amount of hematite (an iron oxide) and slag waste (a smelting byproduct) found there.

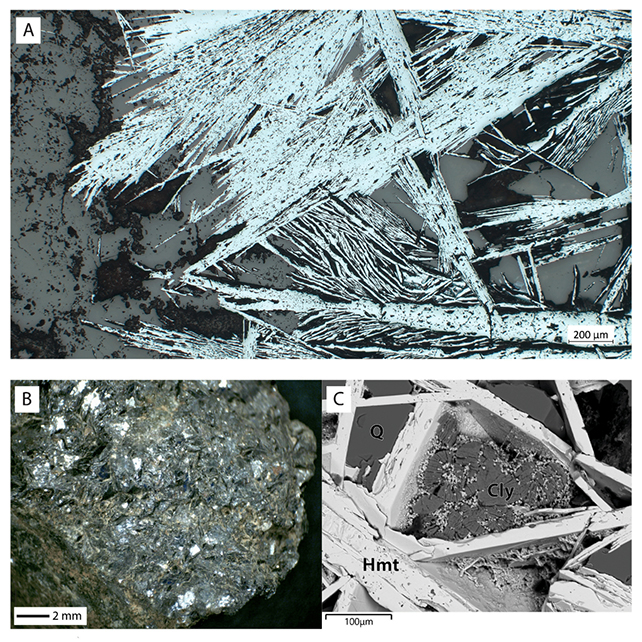

Using chemical analysis and microscopic imaging techniques, the researchers came to a different conclusion: iron oxide was actually used as a flux, a substance added to smelting furnaces to improve, in this case, copper production.

Related: Iron Age DNA reveals women dominated pre-Roman Britain

This then suggests that iron was discovered through experimentation in copper smelters, rather than being developed separately. This is something that has been hypothesized about before, but without much direct evidence to support it.

“This is evidence of intentional use of iron in the copper smelting process,” says Erb-Satullo. “This shows that these metallurgists understood iron oxide – the geological compounds that would eventually be used as an ore for smelting iron – as a distinct material and experimented with its properties in the furnace.”

“Its use here suggests that this type of experimentation by copper workers was crucial to the development of iron metallurgy.”

Once it began, the Iron Age – spanning 700 years – marked a significant period of change and disruption for humanity. Farming became more efficient, combat became more brutal, and new tools were developed with this hard, durable metal.

Of course, this is only one place and iron production probably developed differently in different places. However, researchers are making comparisons with other similar sites, including one in Israel.

It may also be significant that iron minerals are often found in the same locations as copper deposits, making it more likely that copper smelting processes also regularly involve iron elements.

“Iron is the world’s preeminent industrial metal, but the lack of written records, the tendency of iron to rust, and the lack of research into iron production sites have made it difficult to trace its origins,” says Erb-Satullo.

“That’s what makes this Kvemo Bolnisi site so exciting.”

It’s a fascinating period in history, one that is constantly reevaluated. A host of other factors, including supply routes, trade deals, and political unrest, must also be considered when examining the age transition.

As analytical techniques and tools continue to improve, it gives experts a reason to go back and re-examine archaeological sites, including that of Kvemo Bolnisi, which has revealed new secrets decades after its first discovery.

“There is a beautiful symmetry to this type of research, in that we can use the techniques of modern geology and materials science to get into the minds of ancient materials scientists,” says Erb-Satullo.

“And we can do all this through the analysis of slag – a mundane waste that looks like funny-looking pieces of rock.”

The research was published in the Journal of Archaeological Sciences.