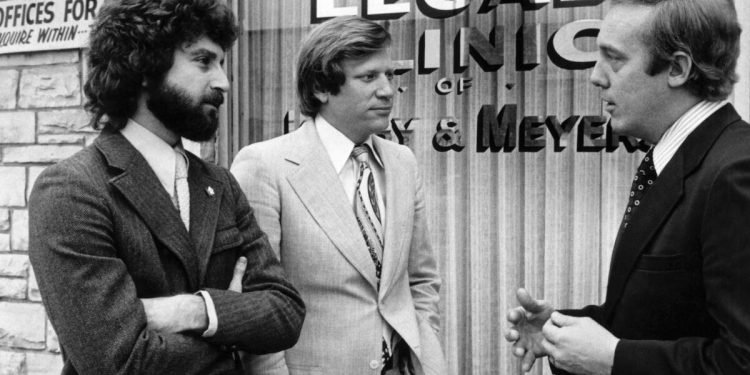

Leonard Jacoby, part of a law firm duo that pioneered lawyer advertising and revolutionized their industry, has died at age 83.

He died Monday in New York from complications of cardiac arrest, according to his wife, Nancy Jacoby.

Jacoby & Meyers, the company he co-founded, is now a mainstay on billboards across the country. They were among the first to offer legal services to the middle class, soliciting clients through a then-unprecedented advertising campaign that would become the model for thousands of law firms.

Today, it’s hard to turn on the television or walk a few blocks in Southern California without seeing an ad for a lawyer. In 1972, when Jacoby and UCLA Law School graduate Stephen Meyers started their practice, no such advertisements existed. Lawyers couldn’t even talk to the press about their firms.

Nonetheless, the duo decided to hold a press conference to announce the opening of their “legal clinic” in Van Nuys, considered the middle-class hub they hoped to make their target market. The rich could afford a lawyer, they believed, while the poor could get free legal aid. It was the Californians stuck in the middle who had no one.

They wanted to change the game with low-cost, high-volume legal services. They accepted credit cards, offered flat rates, stayed open late, and set up desks in department stores. Journalists at the time called it the legal equivalent of a Big Mac: “a fast, simple and convenient service at low cost”.

The state bar hated the press conference, sanctioning the duo for what it considered an act of unethical and distasteful publicity.

“You can’t imagine it was so different,” Nancy Jacoby said. “The lawyers who practice in these expensive firms were dismayed. »

That disciplinary action sparked what would be a years-long feud with the state bar over a lawyer’s right to advertise. They took the case to the state Supreme Court, which held that the lawyers’ right to speak about their services to the media was protected by the 1st Amendment. Soon after, the United States Supreme Court opened the floodgates for lawyers to broadcast their names and faces everywhere.

Less than a week after the 1977 decision, the company took out its first ad in The Times. Their first television commercial aired that year, introducing Californians to “two guys named Jacoby and Meyers.”

Jacoby and Meyers Law Firm in Pasadena, 1995.

(Damian Dovarganes/Associated Press)

These two guys became an advertising powerhouse with commercials appearing on late night shows, soap operas, billboards and airwaves. They marked themselves “America’s Best-Known Law Firm.”

Jacoby had a particular passion for commercials, said his daughter, Sharre Jacoby.

“It was a lot of fun for him to be on set,” said Jacoby, who remembers his father launching folk commercials, often trying to include his own family photos in the picture. “The goal was to say, ‘Come from all walks of life. It was very important not to have them sitting behind a conference table.

It took time for others to understand. According to a survey by the American Bar Assn. taken five years after the Supreme Court’s decision, only 9% of lawyers applied. Most still found it inappropriate.

Jacoby and Meyers saw things differently. Their business exploded, first locally, then soon nationally. In January 1979, they opened 11 offices in New York in one week, according to one New Yorker. profile of their unusual economic model. A decade later, they obtained nominal control in a Beastie Boys song. “I have more suits than Jacoby & Meyers.”

Eventually, others caught up.

“What was revolutionary is now the establishment,” Jacoby told a Times reporter in 1996. “We started as revolutionaries and became the establishment. »

Of course, some lawyers may have overindulged in publicity in the decades since. But the harm caused by these excesses, Jacoby said, pales in comparison to the good that was done by opening the legal system to ordinary people.

“I think what some advertising lawyers did hurt a little bit, but I don’t think it takes away from all the good that was done,” Jacoby told the Times. “In general, I think people have the right to be rude.”

The duo’s friendship deteriorated at the end of their career, with Jacoby suing Meyers in 1995 in an attempt to dissolve the partnership after the two parties separated in different parts of the country, Jacoby in California and Meyers in New York. Meyers died the following year at age 53 in a car accident in Connecticut.

Jacoby is survived by his wife Nancy, his daughter Sharre, his son Tom Nelson, his daughters-in-law Laurie Arent and Lindsey Schank and his five grandchildren.

Source | domain www.latimes.com