The right mix of astronaut personalities could make or break future Mars missions.

A new study led by researchers at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey used advanced computer simulations to test how mixtures of different dominant personality traits among crews affect stress, health and teamwork during long-term space missions. The findings, published Oct. 8 in the journal PLOS One, indicate that crews with a broader range of personalities perform better under pressure, which could shed light on how NASA selects and trains its astronauts for Mars.

According to the study, “diversity in team personality traits may contribute to greater resilience under prolonged isolation and operational burden.” To simulate a crew on a 500-day Mars mission using only computers, authors Iser Pena and Hao Chen incorporated psychological theories into agent-based modeling (ABM), which can create decision-making virtual avatars capable of interacting with each other.

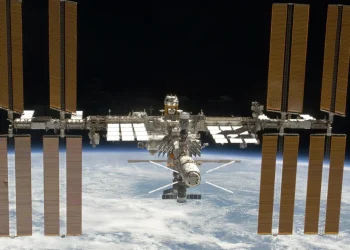

A crewed mission to Mars would likely last at least three years, due to orbital launch and return windows and time spent on the Red Planet. During this time, astronauts will constantly face confined spaces, limited privacy and a grueling workload, all in an environment where they must maintain a professional attitude, clear communication and a cool head with their teammates.

“This new approach allows us to explore how different astronaut personalities and team roles can affect a crew’s stress and performance, and it gives us insight into the human challenges astronauts might face during these long journeys into deep space,” the authors said.

NASA and other organizations are conducting isolation studies and analog missions to better understand these types of interactions and derive methods for predicting crew member compatibility. This new study offers an additional tool to this research and argues that psychological diversity should be as important an operational factor for missions as the reliability of survival equipment.

“There is an urgent and critical need to develop predictive tools capable of assessing and optimizing team composition, psychological resilience, and operational effectiveness under realistic, Mars-like conditions,” the study states.

Pena and Chen’s ABM method tracked interactions between individual “agents” with distinct traits and roles within a shared environment, allowing them to measure larger-scale effects on the team as a whole. The simulation incorporated five major personality traits – open-mindedness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, extroversion and agreeableness – and divided them between different astronaut roles, such as doctor, pilot and engineer.

Teams with mixed personality types consistently maintained better balance and cooperation than homogeneous teams, “indicating that personality and skill diversity can support team resilience in the face of sustained operational demands,” with lower stress levels found in combinations of high conscientiousness individuals and those with low neuroticism, the study authors wrote.

The researchers note that their model has some limitations, such as the characteristics of stationary agents, which do not take into account how individuals might adapt or mature over time. Pena and Chen hope that refining how relationships form, evolve, and break down due to stress will improve future analysis of crew composition.